“They Want to Erase History:” Attacks on Public History and America's National Parks

What was it about a few additions to a single sign that made it so dangerous?

Quick Summary

- A visit to Muir Woods National Monument prompts a reflection on the current attacks on public history and the author's past as a National Park Ranger

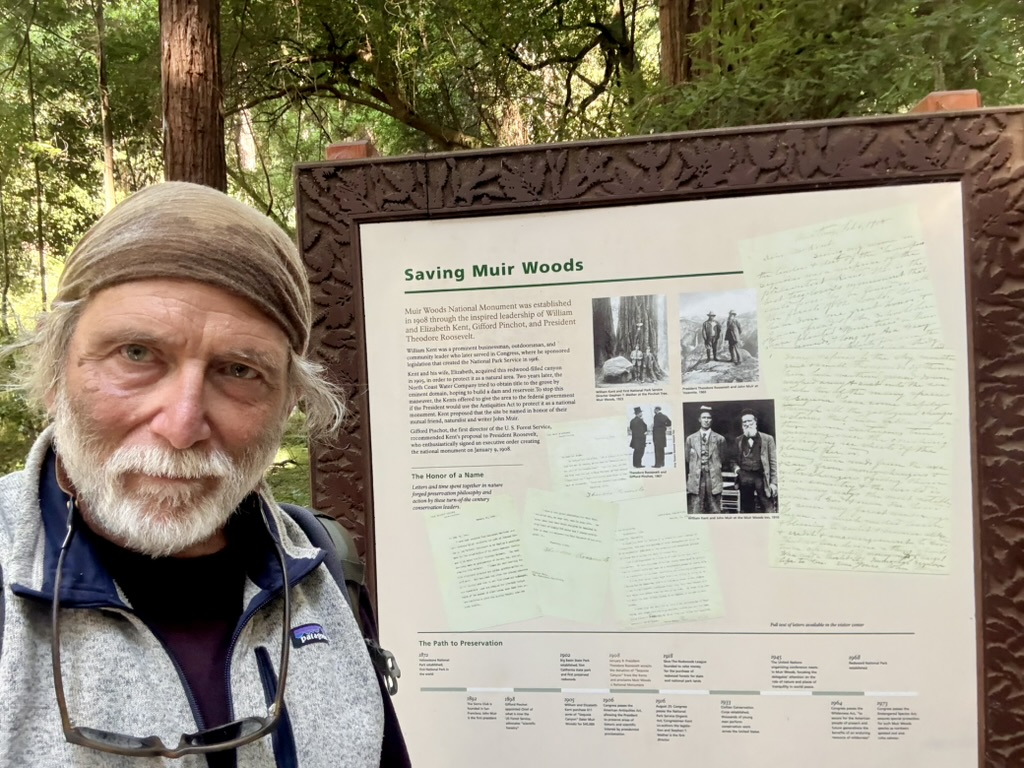

Yesterday I hiked on the Miwok trail from the shoulder of Mt. Tamalpais back to my boat in Sausalito. As I passed through Muir Woods National Monument, I witnessed an early casualty of the administration’s assault on public history.

A sign celebrating the role of wealthy Californians and civil society organizations in the preservation of this old growth redwood forest had been stripped of signage added by Park Service professionals (2021) that had provided visitors with important legal and social historical context.

The additions had been deemed, to quote the 2025 Executive Order 14253 Restoring Truth and Sanity to America History, “negative about past or living Americans.”

I asked a ranger, who for obvious reasons will remain anonymous, why the interpretive staff had been ordered to remove the changes? “They want to erase history,” the ranger replied and added after I expressed concern, “I am here for the public.”

It was a moment of truth and sanity.

What was it about those few additions that were so dangerous they had to be censored? What will be the impact of these kinds of attacks on historical expertise from Muir Woods to the museums of the Smithsonian Institution? What does the erosion of the role of the professional historians and curators in civic life mean for the nature of citizenship and human rights?

As I continued the Miwok Trail, named for a people who call the lands of the vast federal and state parks of Marin their home, these questions troubled me, as did a remembrance of my own time as a NPS ranger in the late 1980s.

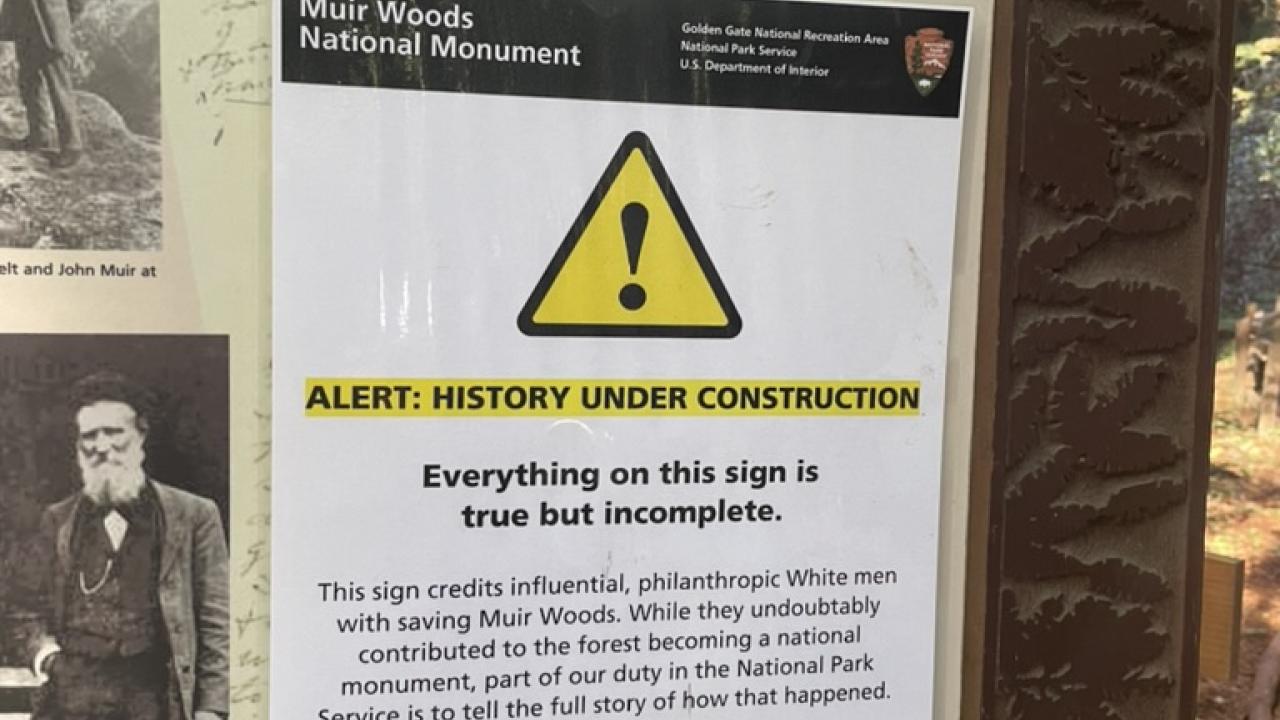

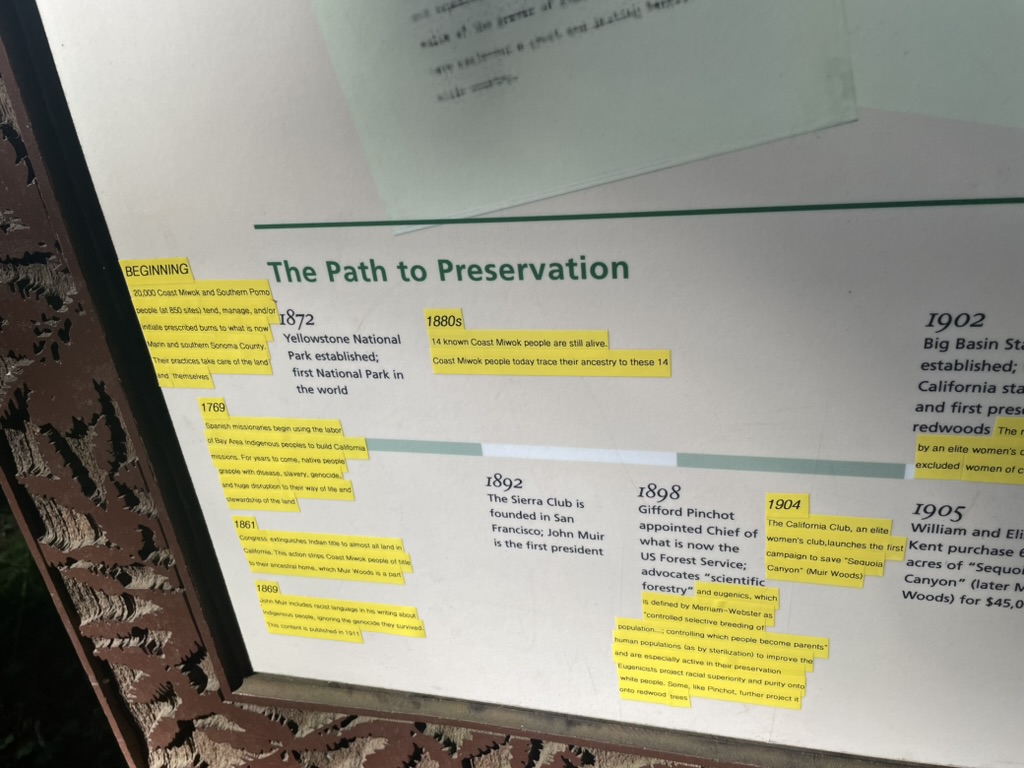

Alert!: History Under Construction — Public History as Civic Dialog

The post-Pandemic, post-Black Lives Matter signage took a witty and engaging approach that imagined history itself was more akin to a construction site than a settled and fixed set of facts. It added to the existing language on the sign rather than removing it altogether, which was the wrongheaded strategy of cancel culture. Rangers pushed the timeline on the sign back to integrate the story the California Missions-era enslavement and genocide of the Miwok people, and critically highlighted the California Land Act of 1851, a federal law that extinguished almost all indigenous land claims. That law paved the way for American colonists to settle the state, and gave power to congress to set aside the land that is now places like Yosemite, Pinnacles and Muir Woods. The signage went further and asked visitors to think about the relationship between conservationism and forms of Progressive-era racial ideology, in particular eugenics.

The land for Muir Woods, like Redwood National Park and Big Basin Redwoods State Park were purchased by very rich Americans and then gifted to the state or federal government — something I find so hard to imagine the robber barons of our era doing.

The added text told us that many of these wealthy Californians practiced forms of discrimination in their political and civic lives, and William Kent, Muir Wood’s main benefactor, was an arch racist, who as a member of congress sponsored anti-Asian legislation and discriminatory land laws. A legacy of the fact that the ultra-elite who established these lands as special places, imagined them as sites of repose only for people like themselves is that non-white visitation to our National Parks remains stubbornly low.

Change has happened in the last decades, the text explained, like the Sierra Club’s rejection of the racism of its founders, including John Muir, for whom the park is named; as well as the restoration of federal recognition of the Coast Miwok, a move that enables access to legal tools for collective rights claims.

An image of the 2021 edited sign is available on the Muir Woods website. For now.

There are elements of the signage I would not have included or not emphasized, but that isn’t the point. The sign didn’t tell me what to think, it challenged me to think about the history of the place where I was standing. “What do the histories we tell say about who we are,” the signage reads “…and who we can become?”

In our current moment that question alone made the sign dangerous — and the fact that the question was being asked of the over 800,000 people who visit the monument annually made it even more so.

Erasing a critical view of a past that combined the acknowledgement of racism and genocide with a discussion of high-minded philanthropy, the conservation ethic and major historical figures like John Muir, is only a problem if one wants systems of racial privilege and discrimination, and systemic human rights abuse to continue. The rangers at Muir Woods had been able to put these elements of history together in a way that pushed visitors to hold possibly contradictory ideas in mind and consequently get more from their experience in the park than just a passing glimpse of the sublime.

What happened at Muir Woods is prologue to a larger fight over the role of history in our public life. As that fight reaches places like the National Museum African American History and Culture the stakes will grow much higher. How will the impulse that led to the erasure of history at Muir Woods play out against exhibits like “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty?”

The Corps of Discovery and Growing a New Historical Language for Civic Dialog

In the late 1980s, I spent a wonderful Summer as a park ranger interpreting one of Jefferson’s most audacious projects, the 1804-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition at what is now called the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. Fresh out the University of Washington with a BA in History and Middle East Studies, I dressed in period clothing, including buckskin breeches; built fires with flint and steel, loaded and shot a Kentucky long rifle and gave talks about the Corps of Discovery and their journey to and from the Pacific Ocean.

It was the perfect job, but it was where I experienced first-hand how much public history is about silencing the uncomfortable and the inconvenient. For example, we were told to explain that after the expedition, Meriwether Lewis, the young co-captain of the expedition was murdered during a robbery gone bad as he journeyed along the Natchez Trace in Tennessee. The historical evidence suggests that it is much more likely that he had committed suicide, which he had attempted before. He suffered from alcohol and opioid addiction and quite possibility major depression. At the time both William Clark and Thomas Jefferson acknowledged his suicide. But when asked what happened by visitors, we told them the less likely version.

We did so because great Americans didn’t have depression or commit suicide, not because it was the true. One wonders if an open discussion about Lewis’ struggles after the expedition could have contributed to a national dialog on mental health and addiction. It certainly would have humanized him and brought added context the emotional struggles he overcame as he led the corps.

The greatest silences surrounded the two enslaved humans who accompanied the expedition. York, Clark’s longtime manservant and the Shoshone teenager Sacagawea, who was in a nonconsensual marriage with the expedition’s translator Toussaint Charbonneau, by whom she had a child. We portrayed them as self-sacrificing heroes who rose above their station to contribute to the success of the expedition and even sanitized their life histories of oppression and exploitation, using by eliding those histories altogether.

The overall story we told was one of great scientific discovery and personal courage. Which was true. We would not have told it as prologue to American settler-colonialism and genocide in the West. Which is also true. At the time, the régime of silencing meant we rangers did not have a vocabulary to explain the other elements of the history. We have that vocabulary now. The professional historians at Muir Woods showed how it could be used.

So much of what is about to happen in museums and parks around the country is born of a vulgar old-fashioned American nationalism — and not ersatz fascism, as some of my colleagues may believe. Plenty of progressive, liberal countries invoke silences around their colonial and racist past. It is the job of historians to approach our past as a construction site, where adding history becomes more important than settling history, and certainly not acting as propagandist for a temporary occupant of the White House. Public and civic historians and museum professionals are especially at risk and need our support.

As I climbed the Miwok Trail to where it crosses the Pacific Coast Highway, a thought kept coming back to me: a self-confident and just nation need never tell lies about its past.