Human Rights Studies for 21st Century Californians

Promoting and protecting the human right to learn human rights is a shared responsibility of our state’s universities and high school system

Quick Summary

- UC Davis Human Rights Studies, Fresno State and the History Project will host a 3rd human rights teacher institute at Cal State Fresno (Saturday Feb. 3, 2024, 9:00 AM - Noon

- In this essay, I explore the origins, theory, and goals of that project and where it fits in the larger field of Human Rights Studies.

Where Should the Human Right to study Human Rights live?

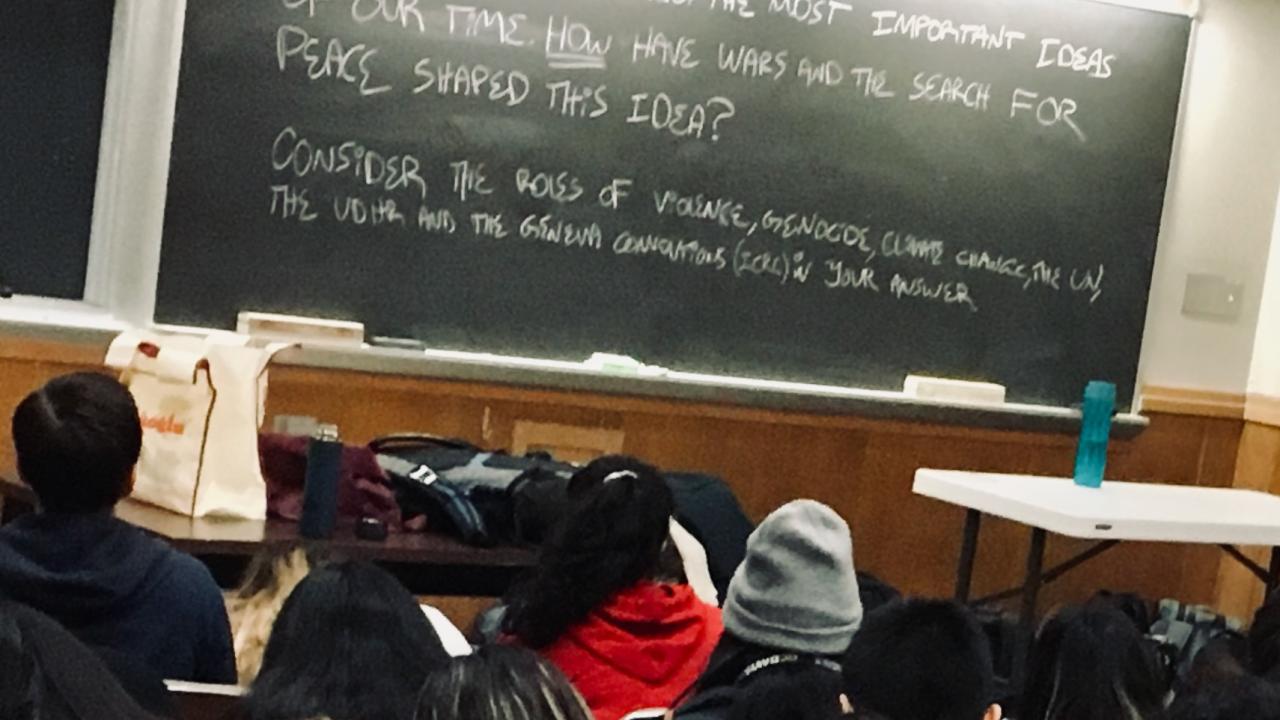

Sometime in the second week of Fall Quarter, I will pose a question to the hundred students in my University of California, Davis upper-division Human Rights Studies core course, Human Rights Studies 134:Human Rights, about their encounter in high school with the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the role of human rights in the 1945 Charter of the United Nations. The UDHR is one of the most consequential documents in our collective history as human beings and is a fundamental building block of the contemporary human rights idea; the Charter establishes the promotion and protection of human rights as one of the purposes of the United Nations and sets the precedent for subsequent human rights treaties and norms. Functionally, knowledge of the UDHR is a good touchstone for whether students have encountered the human rights idea in high school.

In fact, California’s high school student population, which in 2020-2021 numbered some 1.7 million, are required to learn about human rights, the UN and the UDHR, which was unfortunately and tellingly mislabeled the “International Declaration of Human Rights” in California’s 2000 History Social Science Content Standards. Human Rights receives marginal coverage in the most recent History-Social Science Framework guidance from 2016, where for the most part human rights are dismissed as unworkable or irrelevant in the face of Cold War politics, and more contemporary human rights history and discussions of human rights movements and organizations has been put into an appendix. In practice, the relegation pushes the potential of any sustained Human Rights Education to the end of the busy school year and consequently it is often skipped altogether. Without an understanding of crucial moments in human rights history and in the historical context for human rights’ “origin story” the possibility of HRE taking root throughout secondary curriculum is remote.

Asking undergraduates what they remember from high school is an imprecise measure at best. Most commonly, they do remember studying what I would term with a great deal of caution, “human rights-adjacent” topics, including the Holocaust, which for those in Southern California often includes a visit to Los Angeles’ Museum of Tolerance; others recall reading Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s 1973 memoir, A Farewell to Manzanar as part of a unit on World War II-era Japanese Internment; still fewer will remember learning about the 1915 genocide of the Ottoman Armenians. These topics too, are part of the standards-based curriculum, and indeed their teaching is required by law.

Usually, hands go up, just a few, and I think to myself, “this is the year it will be a student from California.” Then the realization comes that the hand belongs to a European exchange student, or young people who studied in elite prep schools in India or Mexico. Those encounters with key human rights terms and ideas are testament to the impactful nature of generations of human rights instruction around the world; it is also a recognition of their countries’ willingness to comply with international treaty obligations to teach human rights under the UN Declaration on Human Rights Education and Teaching (2011) which has its origins in Article 26:2 of the UDHR. In their home country, it is likely that the national Ministries of Higher Education where they come from have coordinated on curriculum with UNESCO and other UN bodies or have drawn on expertise from Human Rights programs at state-supported institutions of higher learning. In the best of cases, the raised hands tell us of a commitment to weave the human rights idea into the day-to-day lives of the people in their homeland, laying the foundations for a lived culture of human rights.

Those of us teaching Human Rights Studies on the post-secondary level have long recognized that when students arrive in our classes, that the history, theory, and criticism of human rights is not something with which they are familiar from their high school years or indeed, have had any exposure to in courses taught elsewhere in our own institutions. The harsh reality is that the overwhelming number of young people passing through US educational institutions will graduate without any formal study of human rights at either the secondary or post-secondary levels, and certainly not in a way that would allow them to distinguish between human rights and civil rights, draw inspiration from human rights achievements, incorporate the human rights idea and knowledge of human rights institutions into the practices of global citizenship. They are neither empowered to use the language and tools of human rights in the work of local and international peace building nor develop a skill set in international human rights advocacy that would prepare them for careers in international human rights or humanitarianism. Most, important, for young people this means that their human right to master and mobilize those ideas and concepts as a social and ethical heuristic and then participate in global solidarity around issues including climate change and social and economic inequality is denied.

While real strides have been made in the last decade, paraphrasing forging the academic discipline of Human Rights Studies a radical disconnect persists between growing interest in the field at universities and colleges and the effective teaching of human rights in American high schools. Even those gains at the level of post-secondary education are tenuous; without the establishment of the Human Rights Program at UC Davis, it is unlikely that any amount of HRE would have taken place on our campus within existing disciplinary and interdisciplinary structures which tend to be resistant to innovation. Clearly, among the most effective ways to secure Human Rights Studies on the post-secondary level over time is to expand and more comprehensively teach human rights at the secondary level and invest in teacher training and professionalization as the critical bridge between the two.

Human Rights Studies for 21st Century Californians Project

Meeting this need is the basis for our Human Rights for 21st Century Californians, a joint project of UC Davis Human Rights Studies, The History Project and collaborators across the state, including Fresno State University. It is supported by the Davis Humanities Institute and the University of California Humanities Research Institute. The goal of the project is to build resources and a support network for Human Rights Studies education in California’s K-14 system.

Delayed by the pandemic, we hosted our first workshop in June 2021 for 10 high school teachers and several UC Davis faculty and History Project Staff. This working document is an outcome of that workshop and was developed to provide a narrative structure around the development of the Human Rights Idea, basic definitions, primary source materials, and discussion prompts. A second workshop was held, again under remote conditions in 2023.

Why a Human Rights Studies Curriculum?

Human rights are an established durable tool for addressing major social, economic and political problems throughout the world. Imperfect as they are, human rights are the only globally recognized touchstone for human freedom, political and civil liberties, and social, economic and cultural rights. When California young people are not aware of the human rights concept, the international institutional and juridical framework for human rights, human rights history, and contemporary human rights organizations and movements, they are left unprepared to take part in these conversations and be part of the solution to the critical problems of our time.

Why Introduce Human Rights Studies into the WWII-Era History/Global Studies Curriculum?

One of the goals of this workshop is to explore introducing human rights and genocide into high school curriculum as part of the larger study of the period 1930-1960.

The modern Human Rights Idea is inextricably linked to events of the Second World War and the Great Depression that preceded it. Exploring human rights as an element to that era places the concept within its proper historical context and provides a more concrete “origin story.” As part of the coverage of WWII and its aftermath, it provides an opportunity to link human rights to New Deal idealism, Japanese internment, and US war aims, on the one hand, and the events of the Holocaust, refugees, the beginning of the Cold War, and the start of decolonization, including the global struggle to end Apartheid, of the other.

Introducing Human Rights Studies in this era, provides a intellectually sophisticate and grounded way to surface voices from underrepresented groups, portray women and US ethnic minorities in key international leadership roles, highlight the place of civil society and religious organizations in human rights advocacy, demonstrate the global origins of human rights, and introduce complex concepts and histories like genocide, anti-Semitism, Jim Crow, the Armenian Genocide, and fascism.

Human Rights provides a language and a structure within which to engage in civil and respectful discourse around larger questions and problems of discrimination, inequality, mass violence, religious freedom, racism, climate justice, and refugees.

Educating young people about their human rights is a requirement of international treaties that our country has signed. More importantly, teaching human rights is a unique contribution that secondary education can make to the promotion of peace and prosperity.

For more information on the workshop and signups; follow this link.